What Happened to the Second Bank of the United States

In the years leading up to the War of 1812, the U.Due south. economy had been on the upswing. The war with Uk, even so, disrupted foreign trade. As one of the United states of america' largest trading partners, Britain used its navy to blockade U.S. trade with other nations. The war prevented U.S. farmers and manufacturers from exporting merchandise, blocked U.S. merchants and fisherman from sailing the high seas, and curtailed federal government revenues, which were derived mainly from tariffs on trade. By 1815, the The states institute itself heavily in debt, much like it had been at the end of the Revolutionary War 30 years earlier.

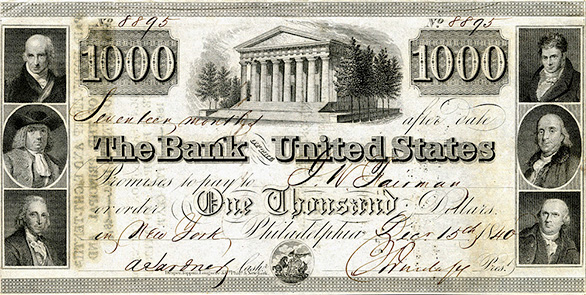

In Jan 1815, the United States had been without a national bank for virtually four years. Many people thought that a successor would again provide relief for the state's ailing economy and aid in paying its state of war debt. Six men figured prominently in establishing this new entity, commonly referred to as the 2d Bank of the United states of america: the financiers John Jacob Astor, David Parish, Stephen Girard, and Jacob Barker; Alexander Dallas, who would become secretarial assistant of the Treasury in 1814; and Rep. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. These men thought that reestablishing a national bank would solve some of the country's economical woes. In particular, Astor, Parish, Girard, and Barker – as lenders and financiers -- felt that a national bank would restore a stable currency, thereby avoiding bouts of inflation and insuring their business organisation interests.

Establishing a Second National Banking company

Despite wide support for reestablishing a national bank, the road to re-creation was non smooth. In January 1814, Congress received a petition signed by 150 businessmen from New York Metropolis, urging the legislative body to create a second national banking concern. In Feb, and again in Nov, Calhoun put along plans to create a depository financial institution that would be headquartered in the Commune of Columbia, but his bills did not pass.

In April 1814, President James Madison, who had opposed the creation of the starting time Depository financial institution of the United States in 1791, reluctantly admitted to the need for some other national banking concern. He believed a bank was necessary to finance the war with Britain. Simply later that year, progress in peace negotiations led Madison to withdraw his support for the proposed national bank.

Later on peace with United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland came in 1815, Congress rejected new efforts to create the bank. In the months that followed, nevertheless, the federal authorities's fiscal position deteriorated amid a broader economic downturn. Many land-chartered banks had stopped redeeming their notes, which convinced Madison and his advisers that the time had come to move the country toward a more uniform, stable newspaper currency. In his annual report, Dallas again called for the establishment of a national depository financial institution. Subsequently much debate and a couple of additional attempts, Madison finally signed in April 1816 an act establishing the 2nd Banking concern of the U.s.a..

Bank Structure and Operations

The Bank opened for business concern in Philadelphia in January 1817. It had much in common with its precursor, including its functions and structure. It would human action as fiscal agent for the federal government — holding its deposits, making its payments, and helping information technology issue debt to the public — and it would issue and redeem banknotes and keep state banks' issuance of notes in bank check. Besides similar its predecessor, the Bank had a twenty-year lease and operated as a commercial depository financial institution that accepted deposits and made loans to the public, both businesses and individuals. Its lath consisted of twenty-five directors, with five appointed by the president and confirmed past the Senate.

The capitalization for the 2nd Depository financial institution was $35 one thousand thousand, considerably higher than the $ten million underwriting of the starting time Depository financial institution. Subscriptions went on sale in July 1816, and the sale period was set at three weeks. To make it easier for investors to purchase subscriptions, sales were held in twenty cities. After 3 weeks, $3 million of scrips remained unsold, so Philadelphia broker Stephen Girard bought them.

The Bank'southward reach was far greater than that of its predecessor. Its branches somewhen totaled twenty-five in number, compared to merely viii for the first Depository financial institution. The all-encompassing branch network aided the country'southward w expansion and its economical growth in several ways. The branches provided credit to businesses and farmers, and these loans helped finance the product of goods and agronomical output as well as the shipment of these goods to domestic and strange destinations. Moreover, the network helped motion the money deposited in the branches to other parts of the nation, facilitating both the government's power to make payments and the branches' ability to supply credit.

Unlike modern central banks, the Bank did not set monetary policy as we know information technology today. It also did not regulate, concur the reserves of, or act every bit a lender of last resort for other fiscal institutions. Nonetheless, its prominence equally i of the largest U.S. corporations and its branches' broad geographic position in the expanding economic system immune it to comport a rudimentary monetary policy. The Bank'southward notes, backed past substantial gold reserves, gave the country a more than stable national currency. By managing its lending policies and the menstruum of funds through its accounts, the Bank could — and did — alter the supply of money and credit in the economic system and hence the level of interest rates charged to borrowers.

These actions, which had effects similar to today'due south monetary policy actions, can be seen most clearly in the national banking company's interactions with state banks. In the form of business, information technology would accrue the notes of the state banks and concord them in its vault. When information technology wanted to deadening the growth of coin and credit, information technology would present the notes for drove in aureate or silver, thereby reducing state banks' reserves and putting the brakes on country banks' ability to circulate new banknotes (paper currency). To speed upwardly the growth of money and credit, the Bank would hold on to the country banks' notes, thereby increasing land banks' reserves and allowing those banks to issue more banknotes through their loan-making process.

Depository financial institution Leadership

The first president of the Depository financial institution was William Jones, a political appointee and a former secretary of the Navy who had gone bankrupt. Under Jones's leadership, the Bank first extended too much credit and then reversed that trend too quickly. The outcome was a fiscal panic that drove the economic system into a steep recession.

When Jones resigned in 1819, shareholders elected Langdon Cheves, an attorney from S Carolina who had served every bit speaker of the House of Representatives, equally president of the Bank. Cheves cut in half the number of second Banking company banknotes in circulation, fabricated fewer loans, foreclosed on mortgages, and exerted more control over the Bank's branches. He presented state banknotes for specie, a request that sent many land-chartered financial institutions into bankruptcy because they did not accept enough gilt and silver on manus to cover the redemptions. Another depression, characterized by deflation and loftier unemployment, ensued. Although the economical slump was part of a worldwide downturn, the Bank'southward policies magnified the contraction in the United states. Public opinion started turning against the Bank every bit many believed it contributed to the recession.

In 1823, Cheves withdrew his name from consideration for reelection to the elevation Bank post, and Nicholas Biddle, a member of a wealthy and prominent Philadelphia family, became head of the Bank. Biddle had previously served on the Bank's board of directors and in the Pennsylvania legislature. With Biddle's guidance, animosity toward the Bank diminished. The Bank contributed significantly to economic stability and growth. Biddle increased the number of notes issued by the Bank and restrained the expansion of the quantity of land banks' notes by pressing them to redeem their own notes in specie.

The Boxing Over the Second Depository financial institution

In 1828, Andrew Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans and a determined foe of banks in general and the second Depository financial institution of the United States in particular, was elected president of the The states. Jackson'southward dislike of the Bank may have been fueled by rumors that Henry Clay, a congressman from Kentucky, was manipulating the Bank to help Jackson's opponent, John Quincy Adams, but it did not rise to a major campaign issue.

In contrast, the election of 1832, which sent Jackson back to the White House, put the Bank in the spotlight. A request to renew the Bank's charter was sent to Congress in January 1832, four years before the charter was set to expire. The legislation passed both the House and Senate, simply it failed to garner enough votes to overcome Jackson's veto.

Why was Jackson so opposed to the Bank? On a personal level, Jackson brought with him to Washington a potent distrust of banks in full general, stemming, at least in part, from a land deal that had gone sour more than ii decades before. In that bargain, Jackson had accepted newspaper notes — essentially paper money — every bit payment for some land he had sold. When the buyers who had issued the notes went bankrupt, the paper he held became worthless. Although Jackson managed to save himself from fiscal ruin, he never trusted paper notes again. In Jackson's opinion, only specie — silver or gold coins — qualified every bit an adequate medium for transactions. Since banks issued newspaper notes, Jackson plant cyberbanking practices suspicious. Jackson also distrusted credit — another function of banks — believing people should not borrow money to pay for what they wanted.

Jackson'due south distrust of the Bank was also political, based on a belief that a federal institution such equally the Bank trampled on states' rights. In improver, he felt that the Depository financial institution put too much power in the easily of too few private citizens -- power that could be used to the detriment of the government. The Depository financial institution too lacked an constructive system of regulation. In other words, it was likewise far outside the jurisdiction of Congress, the president, and voters.

Biddle, who served equally president from 1823 until the Banking company's demise in 1836, refused to accept any criticism of the Banking company's operations, especially claims about the mismanagement of some of the Bank'southward branches. He as well was not above allowing the Banking company to make loans to his friends while denying loans to those less friendly. These actions subjected the Bank to public criticism. Despite all this, Biddle was an fantabulous ambassador who understood cyberbanking.

Jackson saw his 1832 win as validation of antibank sentiment. Shortly later on the election, Jackson ordered that federal deposits be removed from the second National Bank and put into state banks. Although Jackson's order met with heavy criticism from members of his administration, nearly of the government's coin had been moved out of the Banking concern by late 1833. The loss of the federal government's deposits acquired the Depository financial institution to compress in both size and influence.

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, Biddle responded to Jackson's action past announcing that the Depository financial institution would (or could) not respond to the loss of government deposits by attracting new private deposits or raising new capital. Instead, the Banking concern would limit credit and call in loans. This wrinkle of credit, he believed, might create a backfire against Jackson and forcefulness the president to relent and redeposit government funds in the Bank, perhaps even renewing the lease. Only Biddle's motility backfired: in the end, it helped to support Jackson's claim that the Bank had been created to serve the interests of the wealthy, non to meet the nation'due south financial needs.

Closing of the Second Depository financial institution of the United States

One event that foreshadowed the Bank's demise was its supporters' disability to muster a two-thirds majority to override Jackson'southward veto in 1832. More damaging was the removal of federal deposits in 1833, resulting not only in a reduction in the Banking company's size but as well in its power to influence the nation's currency and credit. In April 1834, the Firm of Representatives voted confronting rechartering the Banking company and confirmed that federal deposits should remain in land banks. These developments, coupled with Jackson'southward determination to practice away with the Bank and the widespread defeat of the pro-Bank Whig Political party in the 1834 congressional elections, sealed the Bank'due south fate.

Information technology would be more than seventy-five years before the United States made some other attempt to establish a central bank. During that period, the U.S. economy experienced several banking crises. But after the Panic of 1907, which triggered a nationwide suspension of payments and a deep recession, Congress established a commission to wait into means to ameliorate how the cyberbanking system responsed to the shocks. The commission's findings led to the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

This commodity is adapted from the Federal Reserve Depository financial institution of Philadelphia's publication "The Second Bank of the United States: A Chapter in the History of Central Banking." To order print copies of the publication visit https://www.philadelphiafed.org/education/publication-orders

Image of Custom House by J.C. Wild, printed by John T. Bowen, c.1848, courtesy Library Company of Philadelphia, accession number P.2227

Source: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/second-bank-of-the-us

0 Response to "What Happened to the Second Bank of the United States"

Post a Comment